Brand activism, or belief-driven value marketing to use the adverspeak, where a company positions itself as taking a stand on hot socio-political topics, is not a new phenomenon but is dominating PR strategy in many a boardroom right now. Ordinarily presented through compellingly right-on and emotive copy, ‘radical’ celebrity endorsement, or other disruptive messaging, it is more traditionally attached to entities with a vested interest in such matters: charities, NPO’s, public issue campaigns, but it is increasingly cementing as a recuperative branding device in corporate and consumer marketing.

We are all (mostly) alert to the typical devices employed to get us parting with our hard earned paycheques. We are wise to the game, and we can smell it when we are being patronised or misled. The message here is simple, by all means paint a colourful, nourishing picture of how much you care, but do care. Don’t get caught just acting like you do. If a company is going to align itself with certain beliefs we would clearly prefer this to be done in ernest, and not just adopted as a surefire profit-bump based on psychographic insights generated among the algorithmic-basement-super-brains housed at your Edelman’s, Kantar’s, and Nieslen’s of the world.

Last week, Iceland supermarket were denied the right to broadcast their seasonal ad because it carried too ‘political’ a message for the advertising standards gatekeeper Clearcast. The content of the ad, a rebadged Greenpeace film narrated by Emma Thomson, pits an animated orangutan against a young girl who feels affronted about her room suddenly being occupied by said orangutan. This serves as reflection for the orangutan’s lost natural forest habitat to the aggressive machinery of a palm oil plantation – Iceland stopped using palm oil in its own brand products some time ago. A moral position to take no doubt, but seemingly this corporation is not permitted to make such a political statement on the airwaves. This is interesting on a couple of levels. First, in their defence, what kind of harm is this really doing? Who does this message offend, and who’s interests are really being served by banning it? The main thing for me though, how sympathetic to Iceland’s cause should I really be in the first place?

Take the buzz around the recent Nike Just Do It 30th anniversary campaign. It put the face of Colin Kapaernick up close and personal, and attached the copy “Believe in something. Even if it means losing everything” (in a nutshell, the NFL star who took the first knee to protest racism, in case you’ve been living under a rock). This prompted some backlash; burning shoes, vandalising stores, but this was far out-weighed by a massive 31% sales boost, including a 17% store footfall bump US-wide in the week following its appearance, which is serious ROI for an ad campaign. No ban for political messaging applied here. I’m not arguing which issue is of greater import, but what is the definition of a political message, and when is it OK to align publicly with it?

Edelman released a report this year confirming the increased consumer responsiveness toward value-based marketing. But it doesn’t take big-data-crunching to tell us that we are a fairly switched-on and conscious bunch these days. We all have issues, and issues matter to all of us. Anybody who seems to be aligned with our global outlook gets our vote. Or in the case of Nike, hard-earned paper for leisurewear.

Recuperation

I was preparing to write something on the process of recuperation for some time, with a specific example in mind that caught my attention because it was so cynically executed – more on this in a moment, but with the industry buzz circulating on the wider phenomenon my horizon broadened. Before I roll on in, I do want to make clear that I’m not at all opposed to corporations acting more conscientiously. Quite the contrary. From the hope that being in a position of power and influence change can happen, and it would be nice, if a little optimistic, to believe that year-end dividends were not all that mattered to a firm. But also from the position that things do actually need to be made, and they need to be pitched and sold, and we are living in a time where not just the demands of a competitive marketplace exist, but also the level of intellectual sophistication we humans demand in how we are spoken to. Advertising is not the devil basically. It is necessary and inevitable, so why should it not be more agreeable?

Recuperation then, the jumping off point of which is its antonym détournment – used to define a process were counter-cultural messages are delivered by subverting, or sometimes adopting the typical mechanisms of mainstream corporate communication; culture-jamming, brandalism, insert your preferred nomenclature. The typical purpose being to transmit a socio-political message that may run contrary to the dominant media stream, or perhaps sometimes with no loftier ambition than to disrupt, protest or represent anarchic positions, including anti-capitalist sentiment. Recuperation, put simply is a technique whereby modes of communication, or aesthetic conceits typically associated with sub-cultural or radical values, are coopted and used by corporate entities to position themselves as right-on; that they might be prepared to storm some barricades, or at least that they may have partied a little in high school too. Mainly though, it’s to shake off any potentially icky evil-corp stench. It comes from the same PR playbook as kissing babies, or getting your tribal dance on.

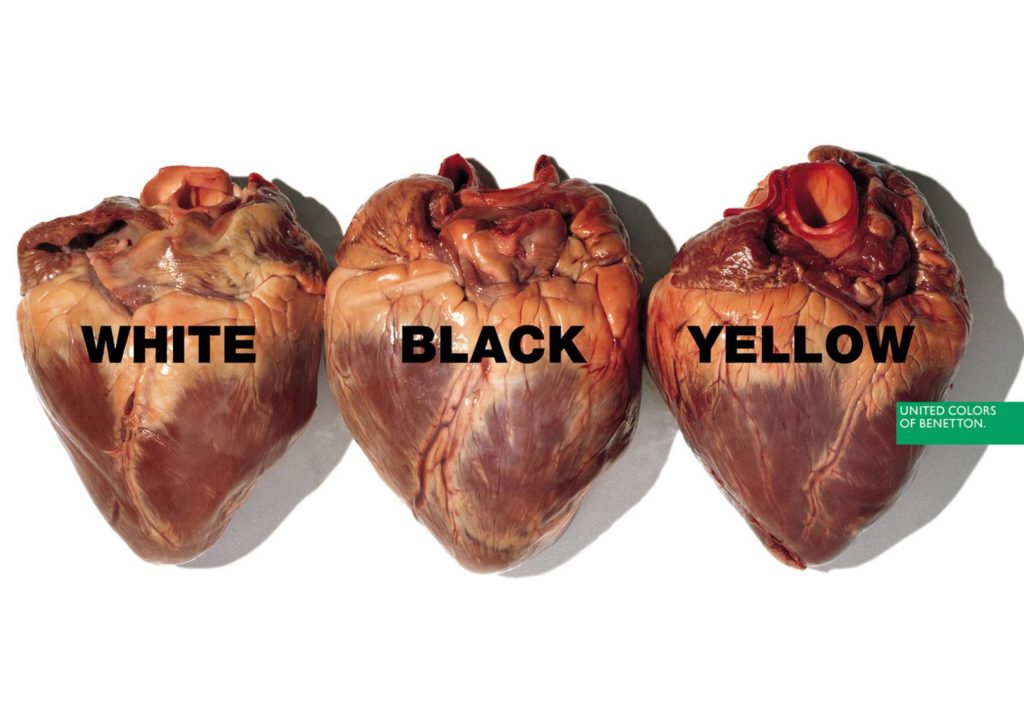

This could include narratives portraying ‘alternative’ lifestyles, maybe off-the-grid, counter-cultural, and often imagery more commonly associated with protest or civil action. It can be quite a tough sell in many cases; Volkswagen pitching the flower power generation, ‘hey hippies buy this gas-guzzler, we painted some flowers on it, man’, and Coca-Cola’s “I’d like to buy the world a Coke…“, spring to mind. Or in more recent cola-comms, and perhaps worst of all might be 2017’s Kendall Jenner ad that shows us how hip, diverse, and urbane types can eradicate oppression with a Pepsi. The standout well-executed example of this line of corporate communication was presented by United Colors of Benetton with their unforgettable, provocative photography-based messaging, art directed by Olivieri Toscani in the 1990’s. This was significant because Benetton decided to use their bandwidth to display broad-reaching, bold visual statements on issues of humanity, race and equality, eschewing talking up their goods almost entirely.

Picking through the semiotics of the Nike campaign, essentially they are identifying with independent ‘free’ thought, and signaling empowerment of the ‘individual’. Which they hope translates into me or you buying some of their kicks to express our individuality, and simultaneously show solidarity with Mr Kapaernick. Presumably we are to focus more on this socially-conscious face, rather than the pittance-paying-sweatshop-overlord face. I don’t mean to snark. Actually, irrespective of their oft-criticised supply chain practices – or insert here a-n-other signifier of corporate black hearts, there should be nothing but nods of approval, because yes it’s a device to drive profits but it’s a win for everyone. It is a huge platform for a very real social issue and surely stands a greater chance of aiding in shifting attitudes forward as a result of the increased exposure.

So Nike done good. So I think did Iceland, but somehow their message is much less immune to the censure of the media watchdogs. What is really at play in determining how much virtue signaling a corporation is permitted to display? In the interest of getting a handle on the parameters, it is worth looking at that example of extremely cynical recuperation I mentioned. Somewhere this censure maybe should have been more rightfully applied. There are many poor examples out there, but in this instance the mantle unfortunately belongs to Bacardi rum.

Segmentation deceit vs. cultural sensitivity

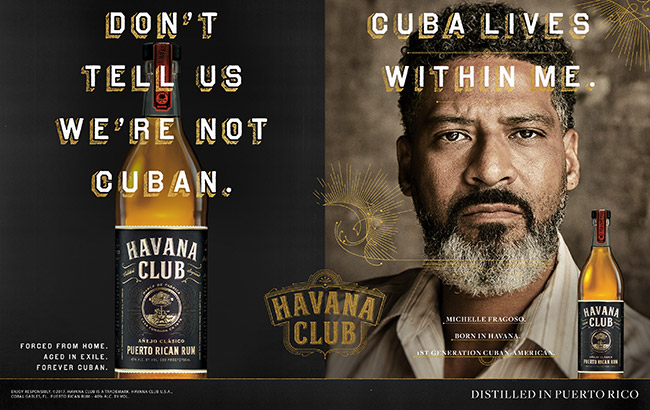

It doesn’t help to focus on the negative in life I know, but frankly, if someone is going to scream in my face, crying foul and presenting their cause as just; demanding my sympathy over their status as lowly and oppressed, when it isn’t true you better believe I’m going to call them out on it. Bacardi’s recent campaign of print and motion ads portray a rather deceitful, and frankly offensive alignment with individuals who are actually oppressed.

What’s all the fuss then? Without going in to a protracted chronology of events, following the Cuban socialist revolution private companies were effectively forced to submit to state takeover. I am neither defending nor denouncing this. The Bacardi family preferred to pursue their capital interests rather than align with the new socialist Cuba, and decamped to Puerto Rico to continue building one of the worlds most successful liquor companies. The original owners of the Havana Club rum product also left Cuba, under debated circumstances, but did sign over their business to the authorities before they left. Bacardi went on to apparently buy the original Havana Club recipe and rights from the Arechabala family some 40 years later. The narrative presented in Bacardi’s advertising gives an image of the freedom fighter, the exiled and suppressed stakeholder who longs for his homeland, a tiny voice, seeking the world to join them in their cry of injustice.

“Forced from home. Aged in Exile. Forever Cuban” reads Bacardi’s Havana Club copy. As I said earlier, belief-driven marketing is not a new thing, back in 2013 Bacardi’s message was their Irrepressible campaign, “Some men are kicked out of bars, others are kicked out of countries”. It is a complex story no doubt, and I am not really trying to dispute Bacardi’s Cuban-ness; though on a side note, there are some juicy conspiracy theories knocking around about their complicity with the CIA and related dirty deeds*, certainly some fairly shaky disputes over their US market-only, and embargo-dodging Havana Club product, pitched against the globally-distributed (and actually made in Cuba) Havana Club. Again, I’m not questioning their authenticity here, and this isn’t about defending the romantic integrity of Che Guevara and the Cuban cause célèbre either. Quite simply, it is entirely inappropriate to appropriate the iconography of revolution and activism against perceived oppressive forces in the interest of capital gains. Full stop.

I have not been able to glean accurate figures on the relative success of these campaigns, but one thing is for certain, Bacardi are not struggling too badly with a current estimated brand value of around $1.9billion, never mind the rest of their business portfolio.So please, if you are rocking a belief-driven brand identity, can it not make me feel so queasy with its painfully transparent cynicism – nor indeed with such aggressive machismo. In the case of Pepsi, who engaged clumsily in recuperation without defining a specific issue, just aping and romanticising the aesthetic of civil action, Bacardi are targeting a specific human identity. No matter how their provenance argument is sliced and diced, this really boils down to a story of protecting global market share, not the plight of a backyard mom’n’pop’s right to earn a humble living, let alone restoring a national identity.

As if to highlight even more how they are simply borrowing this social conscience beret, rather than owning it, they switch up their brand identity on an almost annual basis. To be fair, some of their other hats are genuinely right-on. For instance their SpiritUp ‘music liberates music‘ campaign geared to help promote and develop up-and-coming Caribbean artists. Again of course, this will feed into there bottom line, but at least is an honest, simple and essentially very positive social initiative, Bacardi-brand-awesome. ‘Don’t tell us we’re not Cuban‘, Bacardi-brand-gruesome. This is one aspect of their brand story best left un-leveraged.

The soft power of CSR

If we are going to be presented with a softer side to major players in global commerce, wonderful, but don’t try to make us pity you personally when executive bonuses and shareholder dividends are so blatantly the ‘cause’ we are supposed to be identifying with. Take a leaf out of Nike’s book. It’s not all heart, but credit where it is due, they took a risk and stood on the right side of a very divisive social and political issue. An outstanding example of speaking to, rather than at their consumers. Or indeed from Iceland’s book, where, ironically (intentionally?), their attempt to broadcast an alignment with a globally divisive environmental concern got blocked, simply added even greater rebel notoriety to their brand caché.

There are concerns over how much influence a mega-corp, primarily answerable to their shareholders, should be allowed to exert in socio-political debate. I suppose this is the criticism levelled at Iceland’s commercial, for openly denouncing the palm oil producers which, what, might ultimately affect the economic stability of countries reliant on its production? I feel much more likely would be the potential corporate legal backlash being ducked by the private company entrusted to uphold these advertising standards. Much more plausible than simply coming-a-cropper of clearly hit and miss nanny-statesmanship over public opinion being swayed on the issue.

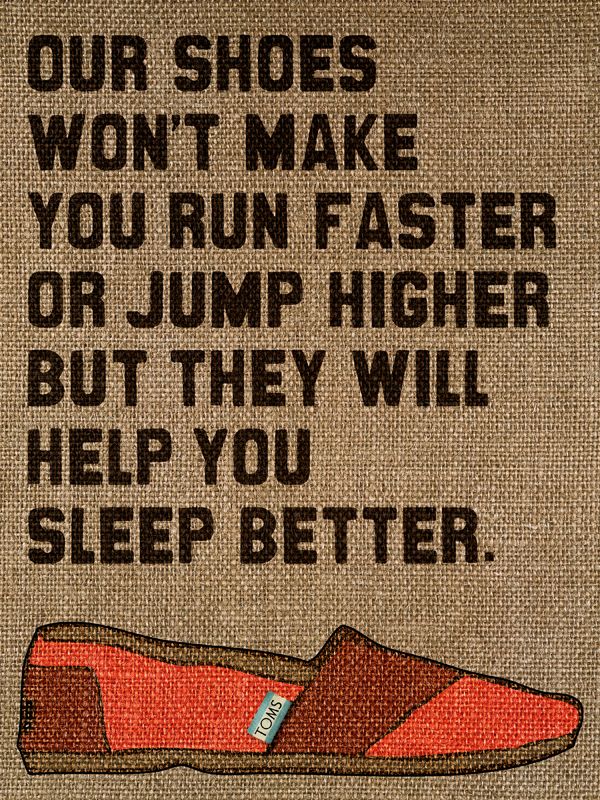

So it will be interesting how much further companies are willing to push their corporate social responsibility, and how much real-world value or change the public see reflected in their neo-radical identities. I welcome the platform. Clearly indy, homespun and smaller scale operators can really go to town on irrerverent and controversial positioning, with lower profiles and investment there is a lot less on the line. In the realms of larger scale global enterprises, the risks are higher, but the mutual rewards are equally so. Companies such as Blake Mycoskie’s Tom’s shoe company, and their ‘one-for-one’ model in delivering developing world aid and eye care solutions for every purchase made, would be a solid example of walking that walk. But they too of course have come in for criticism. There will always be naysayers and snide’s, but I can’t stress enough, doing something is better than nothing. We surely can’t prefer a world where ‘companies should stick to what they know‘, devoted only to collecting the biggest sack of shiny tokens. Is our consumer-based economy going away any time soon? Unlikely. Is it possible we focus on massaging it into being a better version of itself, rather than doom-watching and decrying its existence? At least in the absence of a more persuasive and actionable solution, I’d say so.

We are at a level of meta-consumerism where people in most corners of the world’s leading economies, and to large extents beyond, are totally ready to see their purchasing power directly linked to a dose of social responsibility. In this instance, I am not talking up the merits of people heading towards a state of essentialism, people are always likely prone to indulge, but within that at least I have high hopes this can be leveraged to benefit on all sides. Companies will do well if they respond to this by being willing to genuinely throw down and invest in tackling their chosen causes, beyond superficial bandwagon-jumping and amplifying virtuous soundbites or cosying-up to righteous individuals. Let’s just keep an eye on who’s interests are really being served, how transparent their agenda’s, and we will see who the real revolutionaries may be.

* sources available upon request